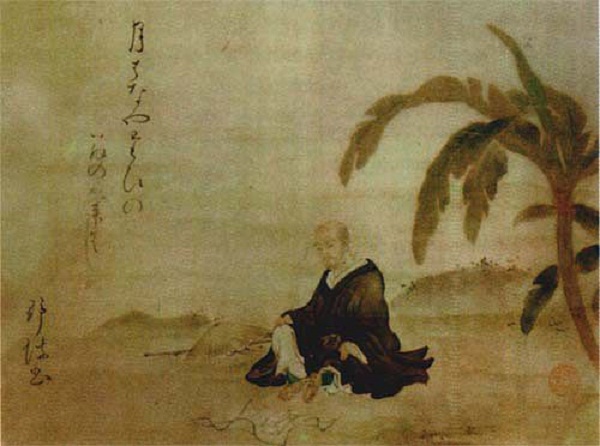

In the second line he says "A hill without a name" (Basho 883). In the first verse he starts out the first line with the single word "Spring" (Basho 883) this word is a symbol of youth. From young to middle age to coming to the fact that time is almost up. In Basho "Four Haiku" he uses many symbols in his writing, with these symbols he uses, he sets up this poem as if it is a journey through life. By use of symbolism in these poems we can see one life start and end and then start a new life for another. Another author that was long after Basho was Carolyn Kizer she uses metaphors in her Haiku "After Basho." All though both these authors are separated by hundreds of years they are brought together with these two poems. Basho wrote "Four Haiku" which use symbolism throughout the poem. One of the most well-known Haiku authors is Matsuo Basho. It is an unrhymed poem that uses aspects of nature, and uses only three lines developing a vivid image. 683-694.Haiku is well known form of poetic writing. “The Narrow Road to the Deep North.” The Norton Anthology of World Literature, Vol. His haiku verses help him capture his emotions – from awe and inspiration to melancholy and boredom – and in the process, he also discovers himself. In The Narrow Road to the Deep North Matsuo Basho sets off to discover Japan, his native country. He paints a peaceful scene of humans just being – where “moon” (693) symbolizes the priest and “clover” (693) the women – suggesting that despite our differences in class and reputation we all share a common humanity. He captures this night with the verses, “Under the same roof / women of pleasure also sleep – / bush clover and moon” (693). One night as he goes to bed, he hears two “women of pleasure,” who are also on a pilgrimage of their own, conversing with an old man in the neighboring room (693). He also writes about being forced to stay “in the middle of a boring mountain” and in doing so allows us and himself to also experience the more mundane and earthy aspects of his voyage (689). In the midst of enchanting or dreamy poetry, “Fleas, lice – / a horse passes water / by my pillow” is a more realistic entry, highlighting the difficulty of the road and its often unpleasant aspects (689). He feels a “sense of reverence and awe” at the Priest’s apparent transcendence (685).īashō’s journey is not only filled with dreamy moments. He finds the reflection of the sun on the leaves particularly inspiring, as if they perfectly embody the meaning of the mountain’s name – as if the Priest had peered from the past into this specific moment in the present. There he writes: “Awe inspiring! / on the green leaves, budding leaves / light of the sun” (685). It used to be called Nikkozan, Two Rough Mountains, but was renamed by the late Priest Kukai as Nikko, Light of the Sun (684). One of the places Bashō visits during his pilgrimage is the holy Nikko mountain.

He mentions Spring to not only mark the starting time of his travel, but also to express his own transition into a novel personal season.Īdditionally, the imagery conjured by these verses – that of animals crying, in particular the fish – emphasize his attunement to nature and sensibility to the melancholy of change. He immortalizes this moment with his first journal entry of the journey, ‘Spring going – / birds crying and tears / in the eyes of the fish’ (684). “Even for the grass hut” emphasizes how nothing in life is invulnerable to change.īashō’s last stop before beginning his journey is Senju, where he is seen off by a crowd (684). These verses articulate his renewed understanding of transience and impermanence as he moves into a new period of his life. Before he leaves and parts with his house, he dedicates a haiku to the event: “Time even for the grass hut / to change owners – / house of dolls” (683). Bashō’s decision to embark on this five-month journey to the deep north is made after he accepts the “summons of the Deity of the Road” (683). He invites us through his poetry to savor the experience with him. He connects with nature, the past, and his inner self on this exciting adventure and uses haiku to immortalize his feelings and discoveries. In his travelogue The Narrow Road to the Deep North, he recounts the experience of travelling with his friend Sora and becoming a tourist in his own country. Though for many of us such desires never actually materialize, Matsuo Basho, a Japanese Haiku master of the 1600s, realized his escapist fantasy when he embarked on a pilgrimage to explore the Japanese Deep North.

Most of us have probably experienced at least once a desire to escape everything – our homes, our responsibilities, our banal lives.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)